On World Habitat Day, celebrated on Monday, 7 October, in Mexico, it is essential to reflect on the future of our cities beyond 2030. Today, in a world turned upside down by the violence of war, threatened by climate change and lifestyles that compromise sustainability, and driven by profound economic and social inequalities, the balance of cities is crucial if we are to chart a future away from the dystopia that is looming.

I want to draw attention to a global crisis that represents a real-time bomb in our cities in the North and the South: the housing crisis. According to the United Nations, 1.6 billion people live in insecure or inadequate housing. This represents around 20% of the world’s population. This situation is forcing more and more workers to settle on the outskirts of urban centres, exacerbating tensions in the labour market. Unfortunately, this alarming figure is set to double by 2050, due to rapid urbanisation and population growth.

This housing crisis is systemic and has multiple impacts. While the housing crisis is already having a severe impact on the middle classes, who are struggling to find affordable accommodation, the consequences are even more dramatic for low-income people. Housing becomes a daily challenge for these people, synonymous with financial insecurity and impoverishment. Faced with soaring rents, they are often forced to spend a disproportionate amount of their income on housing – sometimes more than 50%, or even 60% in some large towns. This situation forces them to drastically reduce other essential expenses, such as food, health, and education, with severe consequences for their well-being and food security.

The situation is just as critical for the elderly and single women who head families with specific housing needs. Because of their low incomes or often inadequate pensions, these people face an increased risk of being forced to move. The lack of suitable, affordable housing often forces them to move into more expensive, lower-quality accommodation far from their social and support networks, increasing their isolation and vulnerability. There is also the issue of ‘fuel poverty’, including older people living in poorly insulated homes that are expensive to heat.

These forced commutes reinforce social divisions and contribute to urban segregation, as low-income households are pushed further and further away from city centres and dynamic areas, where job opportunities, services and quality infrastructure are concentrated. This is also impacting the labour market: skilled people working in high-demand sectors, such as health, education or public services, struggle to find affordable housing close to their place of work. As a result, the housing crisis is not limited to a simple lack of access to housing; it has systemic effects on social cohesion, health, the local economy, and the sustainability of cities.

Faced with these challenges, concerted action is needed. We must promote inclusive and affordable housing policies and rethink our urban models to ensure fair access to decent housing. This is a significant challenge, but building a sustainable and equitable future for all is crucial.

Prioritising proximity to services is crucial for building resilience in the current housing crisis and urban challenges. Living close to essential services such as schools, health centres, shops, green spaces, and public transport brings many benefits that directly address the issues of sustainability, social inclusion, and quality of life.

Firstly, proximity reduces dependence on individual vehicles and travel costs. For families living far from urban centres, travel time and transport costs represent a significant proportion of their budget. Reducing these distances and integrating services into living neighbourhoods helps to cut these costs, which is particularly crucial for low-income households. It also promotes a healthier lifestyle, encouraging active travel (walking, cycling) and limiting CO2 emissions, helping combat climate change.

Secondly, better access to public and private services strengthens social equity. When essential services are close by, the most vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, children, or people with reduced mobility, can access the resources they need more quickly. This proximity strengthens social cohesion, encourages diversity, and reduces inequalities by offering everyone similar opportunities for healthcare, education and leisure access.

What’s more, proximity fosters neighbourhood economic resilience. A dense local fabric of services, shops, small businesses, and artisans creates local jobs and stimulates the local economy. Well-serviced neighbourhoods are more resilient to economic shocks because they generate short production and consumption circuits, making communities more autonomous and less dependent on external economic flows.

Finally, easy access to services is a key factor in quality of life. Proximity encourages social interaction, strengthens neighbourhood ties and fosters a sense of belonging and security. People have more time for social, cultural, and family activities, contributing to their well-being.

The proximity of services is a powerful tool for developing more resilient cities, capable of dealing with social, economic, and climatic crises. It helps to create inclusive, sustainable urban environments adapted to all citizens’ needs, while offering concrete solutions to the housing crisis and the urban challenges of the 21st century.

As part of this approach to creating multi-service proximity in a polycentric and interconnected city, a medium- and long-term policy must be developed to ensure the availability and affordability of housing, while promoting social diversity through a combination of policies and innovative measures.

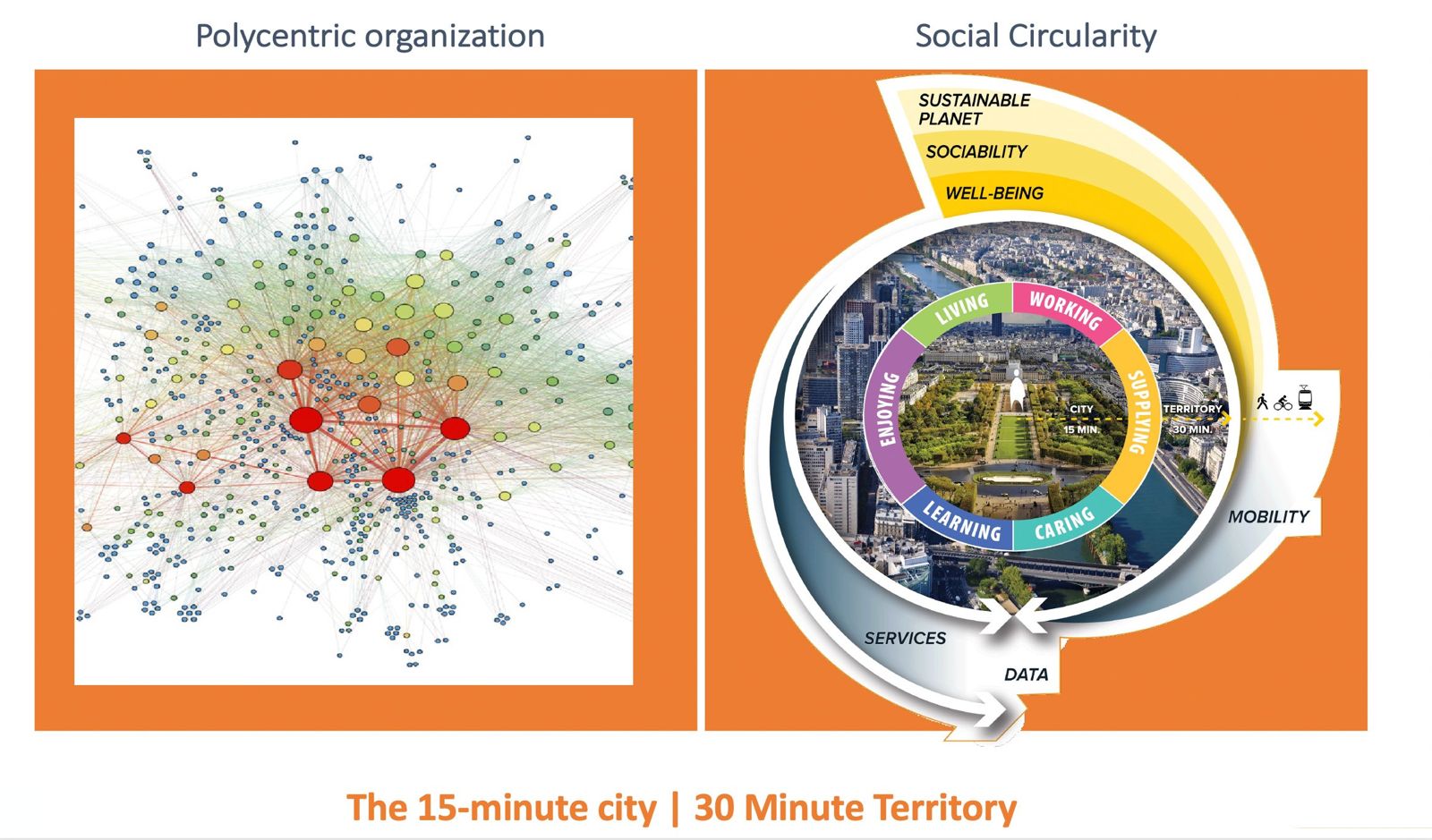

“Proxilience”, or the geographical economy of sustainable proximity, is emerging as a central urban strategy for strengthening cities’ resilience in today’s systemic challenges. By focusing on polycentric proximity, this approach aims to create urban environments where residents have rapid access to essential services, where the local economy is robust, and where mobility is fluid, thus contributing to greater social cohesion and less dependence on external resources.

By encouraging a local economy, “proxilience” promotes short supply chains and the revitalisation of neighbourhoods. Bringing production, sales, and consumption closer together reduces transport costs and greenhouse gas emissions and reduces dependence on globalised supply chains that are vulnerable to crises. Developing local shops, farmers’ markets, and craft activities strengthens the urban economic fabric while stimulating employment. According to the OECD, strengthening local economies can reduce import dependency by up to 30%, increasing economic resilience in the face of global disruption.

Proximity also contributes to greater social inclusion. Integrating social and functional diversity into neighbourhoods ensures all residents have equitable access to services such as schools, health centres, shops, and leisure facilities. This approach contributes to developing community solidarity links and support networks, improving social cohesion, and offering fairer economic opportunities for all. According to the World Bank, neighbourhood-focused cities increase access to services and jobs for marginalised populations, while improving social interaction and quality of life.

Regarding mobility, “proxilience” focuses on soft and inclusive modes of travel, such as walking, cycling or public transport, reducing dependence on the private car. This reduces traffic congestion, improves air quality, and frees up space for user-friendly uses such as pedestrian zones, cycle paths and green spaces. Cities that invest in soft mobility have reduced their CO2 emissions linked to travel by 15 to 20%, while improving the health and well-being of their residents.

We also promote this approach as an effective response to the housing crisis. By promoting multifunctional neighbourhoods, it facilitates the construction of a variety of housing types (social, affordable, and family) while encouraging their integration into a vibrant and connected urban fabric. This brings residents closer to services, reduces transport costs and frees up resources for other essential needs. The proximity of housing to services and economic opportunities thus contributes to social diversity, equity, and resilience.

This proximity encourages local sustainability in terms of food and energy. Creating urban gardens, vertical farms, and food cooperatives strengthens neighbourhood autonomy and reduces dependence on imported products. Using local renewable energies, such as solar panels and district heating networks, increases cities’ energy resilience to climate shocks and market fluctuations.

Finally, « proxilience » represents a response to global shocks through local resilience. By relying on local solidarity networks, a diversified economy, and accessible public services, towns and cities can overcome social, economic, or climatic crises. This vision enables communities to adapt quickly, protect their residents and maintain a high quality of life. Sustainable proximity thus becomes a powerful tool for building inclusive, autonomous, and sustainable cities where quality of life, equity and sustainability are at the heart of urban development.

Here are ten ways this approach can help develop a comprehensive approach to housing, responding to the systemic housing crisis.

1. Encouraging the construction of social and affordable housing

The construction of social and affordable housing must be a priority to meet the needs of low- and middle-income populations. Public policies can stimulate this construction by imposing affordable housing quotas in every new housing project and by offering tax incentives or subsidies to property developers who commit to this type of development.

2. Promoting a mix of housing types

Social and functional diversity must be integrated into urban planning from the design stage of housing projects. This means designing neighbourhoods that welcome a diversity of households in terms of income, family situation and culture. This can involve building various housing (social housing, intermediate housing, housing for students or the elderly, etc.) in the same neighbourhood. This mix creates more dynamic, inclusive, and resilient communities.

3. Reinforcing renovation, refurbishment, conversion, and multi-purpose use for more housing

In addition to constructing new housing, it is essential to transform mono-functional areas to provide more housing with a social, functional, and mixed-use mix. This includes renovating old buildings to make them habitable, energy-efficient, and affordable to increase the supply of housing available at a moderate cost.

4. Promoting participative housing and cooperative housing

Participative and cooperative housing models offer exciting alternatives for creating affordable housing while promoting a social mix. In this model, residents are involved in the design and management of their homes, which reduces construction costs and ensures an inclusive and supportive environment. Cooperative housing also helps to protect homes from property speculation by encouraging collective ownership or long-term rental models.

5. Regulating rents and combating property speculation

In many towns and cities, rising rents and property speculation make housing unaffordable for many of the population. Rent controls, such as price caps and rent increases controls, can help stabilise housing costs. At the same time, combating speculation and purely profit-making investments (such as second homes or properties bought to be left vacant) can free up more housing on the rental market.

6. Innovative financing and ownership models

Alternative financing and ownership models can play a key role in making housing more affordable. For example, rent-to-own (or ‘leasing’) allows households to acquire a home gradually. At the same time, community land trusts guarantee collective ownership of the land and leave homes available for affordable rent. These models offer flexibility that can be adapted to the needs of different social categories.

7. Developing public-private partnerships

Collaboration between the public and private sectors is essential for implementing affordable housing projects. Public-private partnerships can mobilise financial, land and technical resources to develop affordable housing. In exchange, public authorities can put in place obligations to ensure that these projects contribute to social diversity and meet accessibility and sustainability criteria.

8. Using public land to create affordable housing

Land represents a significant proportion of the cost of housing. Local authorities can encourage affordable housing development by making public land available on favourable terms, provided that the projects meet affordability and social mix criteria. This reduces construction costs and ensures fair access to housing.

9. Making neighbourhoods more attractive and well served

To encourage social diversity, it is crucial to develop neighbourhoods that offer a high quality of life, accessible services (schools, health centres, shops), high-quality public spaces and efficient public transport. Social diversity will be all the easier to achieve if all of a city’s neighbourhoods, and not just the centre, offer satisfactory living conditions, enabling households of different income levels to settle there and flourish.

Combining these different strategies makes it possible to promote the creation of affordable housing while encouraging social diversity, thereby contributing to more inclusive, resilient and equitable cities.

10. Combating vacant accommodation and tourist speculation linked to rental platforms

A significant factor contributing to the housing crisis is the increase in unoccupied housing or housing diverted for short-term tourist rentals via online platforms (such as Airbnb). In many cities, these homes, initially intended for permanent residents, are being converted into temporary rentals, leading to a reduction in the supply of available long-term accommodation and a rise in rents.

Integral housing is much more than just housing or having a roof over your head and four walls. True urban living means living with dignity, with access to essential services, in inclusive neighbourhoods that encourage a social mix. It means adopting an approach centred on proximity, where short distances become the key to a better quality of life, greater social cohesion, and a sustainable and resilient urban environment. It’s a forward-looking approach that calls for developing coherent public policies to achieve this objective: building an actual city for everyone!

–

*Scientific Director of the ETI Chair, IAE Paris Sorbonne, Université Paris1 Panthéon Sorbonne